Gilberts Syndrome And The Brain

Fatigue, brain fog, and sleep problems are some of the most common — and most misunderstood — symptoms of Gilbert’s Syndrome. In this blog post we explore how Gilbert’s Syndrome may affect the brain and nervous system, and why fatigue in GS often feels deeper than “just being tired.” We’ll look at emerging research on brain chemistry, glial cells, and neurotransmitter balance, and how these subtle changes could contribute to exhaustion, cognitive fatigue, poor stress tolerance, and sleep disruption.

SYMPTOMS

12/20/20255 min read

Gilbert’s Syndrome & the Brain

Why Fatigue Is So Common in GS (and Why It’s Not “Just Fatigue”)

I won’t lie — this was a hard one for me to write.

Originally, I wanted to talk about mental health and Gilbert’s Syndrome (GS) as a whole, but the more I dug into the research, the clearer it became that fatigue deserves its own spotlight. Not because it’s the only issue in GS — but because it’s often the most debilitating, and the least well-explained.

Fatigue affects roughly 13.5% of adults in the general population and can stem from many different causes. In reality, it’s almost always multifactorial.

In Gilbert’s Syndrome, however, fatigue shows up far more often. Studies report prevalence anywhere from 20–80%, depending on the population studied. That alone suggests something more than coincidence.

In this post, I’ll first touch briefly on fatigue in general, then zoom in on how GS may contribute to it through effects on the brain and nervous system. I strongly believe fatigue should always be addressed from multiple angles — rarely is there a single cause or a single fix. The ideas below won’t explain everything, but they may explain why fatigue in GS feels different.

Common Contributors to Fatigue

Fatigue can arise from many underlying factors, including:

NUTRIENT DEFICIENCIES

Especially:

Vitamin D

Vitamin B12

Iron

Magnesium

Zinc

psst qucik note from torro, youre a lot more likely to have these deficiencies if youve taken antiacids or ppis before like me ;]

HORMONAL IMBALANCES

might be worth checking it out! We know that GS females are more likely to have Estrogen dominance!

These factors matter — but they don’t fully explain why fatigue is so persistent in many people with GS.

“Gilbert’s Syndrome Is Harmless”… Or Is It?

Clinically, Gilbert’s Syndrome is often described as harmless. And in a narrow sense, that’s true — GS is not associated with liver failure, seizures, or obvious structural brain damage in adults.

But that conclusion may be incomplete.

People with GS tend to live longer, which historically led medicine to assume that mildly elevated bilirubin had no downsides. The only time bilirubin is widely considered dangerous is in infancy, when jaundice can cause severe neurological injury because the brain is still developing.

However, absence of catastrophic damage does not equal absence of effect.

Just because adults with GS aren’t experiencing kernicterus doesn’t mean nothing is happening, especially at the level of brain metabolism, neurotransmitters, and energy regulation.

Each new study seems to get a little closer to this idea.

After reading a large body of research, I’ve come to see four overlapping theories for how GS may contribute to fatigue. Some are directly supported by data; others help connect the dots. While more research is still needed, what’s striking is that the potential solutions overlap, regardless of which mechanism turns out to be most important.

WHAT IS FREE Bilirubin?

Gilbert’s Syndrome causes elevated unconjugated bilirubin due to reduced activity of the UGT1A1 enzyme.(If this is confusing, I recommend reading GS Basics first.) To understand what comes next, we need to talk about free bilirubin.

Free bilirubin is a type of unconjugated bilirubin.

Normally, unconjugated bilirubin is bound to albumin, which is essential. Without albumin, bilirubin could freely enter cells and cause widespread damage.

Think of it like this:

Albumin is the shell

Free bilirubin is the pearl inside

As long as the pearl stays inside the shell, it’s relatively safe.

But sometimes, the pearl slips out.

Free bilirubin is extremely small and lipid-soluble, which means it can cross barriers that usually block toxins—including Blood–neural barriers [The ones that separate the blood and nervous system]

The blood–neural barriers are protected by an incredibly strong defense system designed to keep harmful substances out—including bilirubin.

In earlier theories, I wondered whether these barriers might be “leaky.” Research does suggest that high levels of unconjugated bilirubin (UCB) can damage blood–neural barriers and create openings. Other factors, such as leaky gut, may also contribute.

However, whether the barrier is leaky or intact may not even be the main issue—because the next piece of evidence is too significant to ignore.

People with GS likely have higher levels of free bilirubin, simply because the body only produces a finite amount of albumin.

(Keep this in mind—it’s important later.)

The Blood–Neural Barriers (Blood–Brain Barrier, etc.)

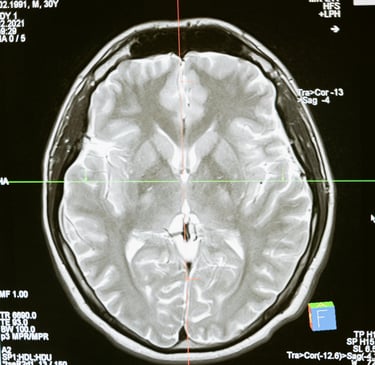

Brain Imaging Evidence in Gilbert’s Syndrome

A fascinating study from Japan used Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (MRS) to analyze brain chemistry in people with Gilbert’s Syndrome.

The researchers found reduced levels of myo-inositol, a marker of glial cell health, specifically astrocytes.

What Are Glial Cells?

Glial cells are non-neuronal cells in the nervous system. They:

Support neurons

Provide nourishment

Protect neural tissue

Maintain the brain’s environment

They make up about 50% of the central nervous system, which is significant.

One specific type of glial cell is the astrocyte (and yes, they’re visually pretty—I’ll include an image).

The Role of Astrocytes

Astrocytes are central to healthy brain function. They:

Support neurotransmitter signaling

Maintain chemical balance in the brain

Protect neurons from overstimulation

Most importantly, astrocytes clear over 90% of glutamate in the brain.

Astrocyte Stress & Neurotransmitter Imbalance

When astrocytes become stressed or impaired, a cascade of effects can follow.

Glutamate may begin to accumulate in the nervous system, while GABA production may not keep up. This leads to a neurotransmitter imbalance.

Glutamate vs. GABA — Why Balance Matters

Think of these two neurotransmitters as opposing forces:

Glutamate is the brain’s “GO” signal — it excites neurons and increases activity

GABA is the brain’s “STOP” signal — it calms neurons and prevents overactivation

In a healthy brain, these systems stay in balance.

In people with GS, available research suggests glutamate may become excessive, while GABA may be relatively insufficient.

How This Imbalance May Feel

A glutamate-dominant state can explain many commonly reported GS symptoms, including:

Fatigue & Exhaustion

Feeling drained despite rest, with persistent mental and physical fatigue

Nervous System Overactivation

A constant “on-edge” state, poor stress tolerance, and exaggerated responses to minor stimuli

Brain Fog

Difficulty focusing, mental exhaustion after small tasks, and slowed processing despite racing thoughts

Sleep Disruption

Trouble falling asleep, fragmented sleep, or waking up unrefreshed

Other symptoms—such as sensory sensitivity and mood changes—may also be influenced by this imbalance.